BEHIND THE LENS APRIL 4 2024

by Anna Carnick

A conversation with revered photographer Hélène Binet

CAN LIS 01 (MALLORCA), ARCHITECTURE BY JØRN UTZON (2019)

Photo by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

When viewed through photographer Hélène Binet’s eyes, the world around us transforms into something at once new and familiar, strange yet sublime. A bridge becomes sinewy, animal-like (as in her photographs of Sergio Musmeci’s concrete masterpiece above the Basento River); a building dons a smile (as in her recent images of a house in the village of Yangdong, South Korea), or is seemingly transported to the moon (as in her early, 1980s depictions of John Hejduk’s work).

PONTE SUL BASENTO, ARCHITECTURE BY SERGIO MUSMECI (2015)

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

The London-based, Swiss-French photographer’s lens captures landscapes, man-made structures, and beyond. She has photographed the work of numerous acclaimed architects, both historical and contemporary—from Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto to Zaha Hadid, Peter Zumthor, and more—consistently honoring the spirit and rigor of their work while also bringing to it a perspective all her own.

In so doing, she draws the viewer in, evoking the aura of a place while also setting our imaginations soaring—reminding us of the pleasure and even awe that can come with thoughtfully peeling back the layers of the spaces with which we engage. As she has said, “I’m not trying to reconstruct the place…I’m more interested in making you dream about the place.”

It seems fitting then, that Hejduk once told Binet he saw in her images the first dream he had when conceiving his work. And Hadid told Binet the images she shot of her existing structures revealed elements that helped inspire her future designs.

On the occasion of a new monograph by Lund Humphries celebrating her work from the past 40 years (and featuring over 170 photographs, many published for the first time), Binet sat down to discuss her creative path, her collaborations, and the meaning that can be found in always pushing oneself farther.

PHOTOGRAPHER HÉLÈNE BINET

Portrait by João Coles

Anna Carnick / When did you first know that you wanted to be a photographer? Was there a particular moment or encounter that set you on your path?

Hélène Binet / I always knew I wanted to be a creative person. I grew up in Rome in the sixties, and my parents are musicians, so there were always many artists around me. I recall thinking that if I went to photography school, I could learn an art but also have a safe profession; it was a very rational choice in a way. My education was quite technical, rather than creative, which I’m grateful for—though it took awhile to find my own path, as photography has so many different branches.

I was really exposed to architecture in the late eighties, through the man I was dating, the architect Raoul Bunschoten, who became my husband. We came to London together and met all these wonderful people, many of them architects, including a young Zaha Hadid, Daniel Liebeskind, John Hejduk, and Peter Zumthor. It was a very vibrant time.

JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, ARCHITECTURE BY DANIEL LIBESKIND

Photo by © Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

“Every time Hélène Binet takes a photograph, she exposes architecture’s achievements, strength, pathos and fragility.”

—Architect Daniel Libeskind

Before then, I’d been searching for my place in photography, but when I encountered architecture and spaces, I felt immediately comfortable. Behind the camera, in front of a building, looking at light and taking my time to reflect, I felt so happy. Maybe it’s because I grew up in Rome, surrounded by beautiful light, and beautiful architecture too. Also it just fits me; it’s slow and meditative. It’s about constructing an image in relation to a particular idea. And I was so thirsty for creative ideas following an education that had been a bit dry—and then to encounter a world that is all about concept and poetry, what more could I have dreamed for? It was a fantastic period.

And pretty early on, I was invited to shoot for John Hejduk, the artist, architect, and educator, which was very important in unlocking the most poetic side of my work.

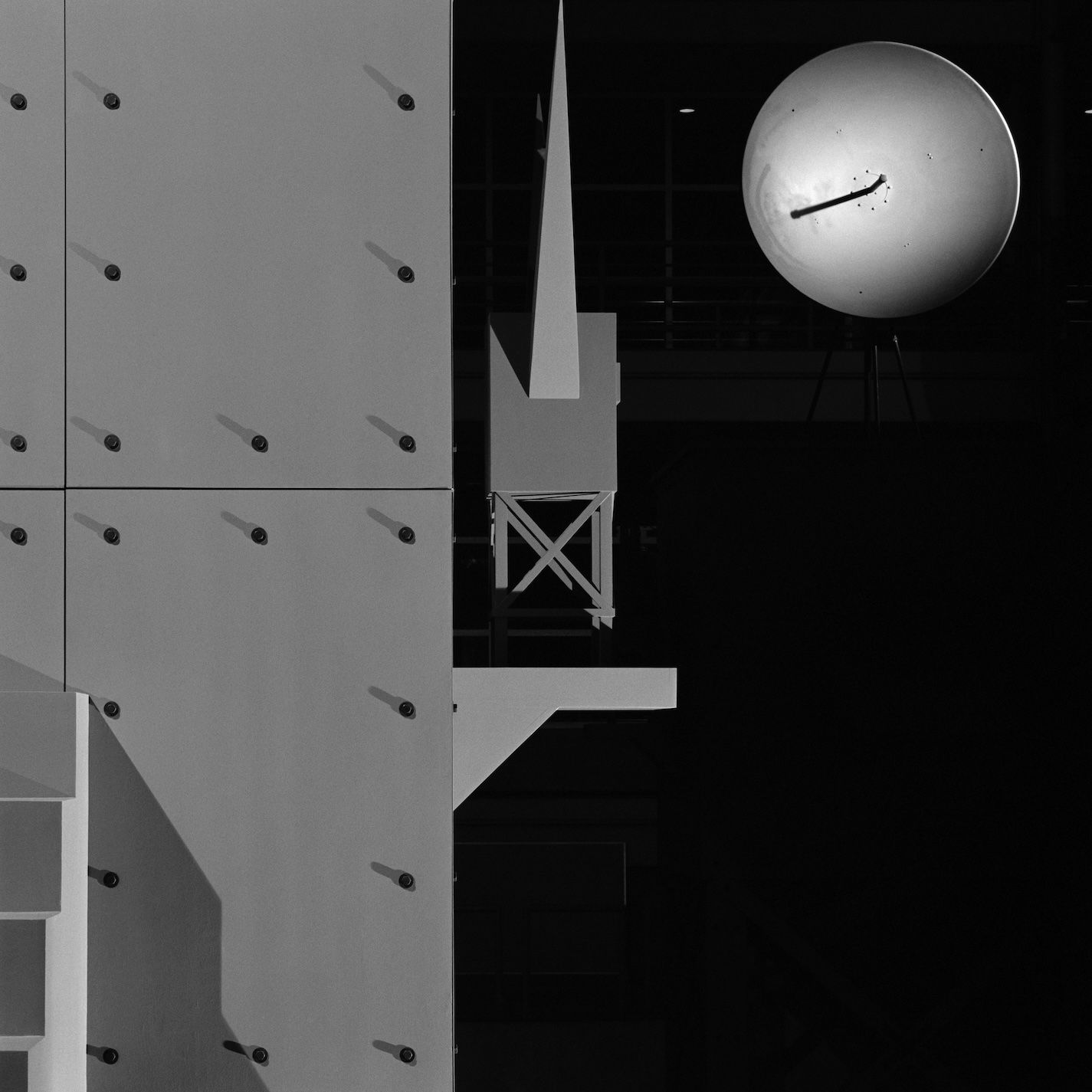

NUMBER 11, JOHN HEJDUK, OBJECT/SUBJECT, FROM THE RIGA PROJECT (1987)

Photo by Hélène Binet

AC / Right. You've said previously that Hejduk’s approach had a great impact on your own. Can you share a bit about that?

HB / He was a very charismatic person; yet there was always a great sense of mystery about him. And his work is so strong, full of so many references, so much meaning. I think just being close to his poetic world helps open one’s eyes. Working with him reinforced my understanding that when you look at something, you cannot stop at the surface. You must look deeper. There is always more to discover.

And that's the beauty of making photography for me, this opportunity to share something that might have escaped someone’s initial perception of a space. Perhaps you look at a place and you feel something immediately, but you don't know exactly why; with photography, I can help a viewer to meditate and get closer to that feeling, and to the spirit or the meaning of a building.

FROM LEFT: LE CORBUSIER'S SAINTE MARIE DE LA TOURETTE - CANONS DE LUMIÈRE AND FIRMINY (BOTH 2007)

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

AC / That reminds me of a quote I recently read of yours. You said: “I’m not an architect; I’m a photographer… I’m not trying to reconstruct the place…I’m more interested in making you dream about the place. It’s like reading a description in a book; you make your own image.” Can you elaborate on this concept of being in dialogue with the world around us—and how you understand photography’s position in this exchange?

HB / Being alive in the world is complex—just think of how our senses are always engaging. There’s so much happening at once, some of which we’re not even conscious of. The role of a photographer is not to try to replicate that, because it’s impossible. Rather, photographers have a very simple tool; we work with two dimensions. I simplify even further by shooting mainly black and white, and focusing on details. Then with those key elements, in my photography, I aim to stimulate the imagination. I want to find a way to help you feel close to the subject, to find in it a line somehow to other experiences in your life, and to allow you to dream. I think your participation—the viewer’s participation—is essential. The reader is always very important in the story.

I recall a beautiful dialogue between John Berger and Susan Sontag years ago in which they talked about storytelling. Berger said that within a story, there are always three key parts. There is the story, what happened—and in my case, this is the architecture. Then there is the writer, and in my case, this is the photographer, with their own subjectivity. And then there is the reader, who finally makes the story come together. And in photography, that's what most interests me, the joining of these three.

MAXXI A, ARCHITECTURE BY ZAHA HADID (2009)

Photo by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann projects

“In her photographs, Hélène Binet allows the viewer to enter the space—not only the architectural space, but also the emotional space.”

– Architect Peter Zumthor

AC / That’s really lovely. So if that union of the three is what interests you most, what gives you the most joy in your work?

HB / I think it’s the moment when I take the image. I work mostly outdoors, and when you’re outdoors, you encounter a lot of stimuli. There are sounds, the light changes, you move up, or down, and so on. Sometimes you see a beam of light falling on a stone that seems perfect, and then by the time you get ready [to shoot], it's over. Sometimes it may take a few days until everything feels like it’s in place, then all the elements converge, and in that one instant, you pray and say ok, this is the moment. It’s very beautiful to me, and quite intuitive. Even joyful. It's about celebrating that specific moment, one that will never exist again. Because there will always be something different.

I study my environment of course, but at that moment when I take the photo, I am just happy. It’s not something I can completely rationalize on the spot. Then, later, in the darkroom, printing is also a special moment. That’s when I can often better understand why I was so convinced by that earlier moment. And when you feel that you have managed to put together all the most essential factors of that place and make it into your own, there is a form of magic to it.

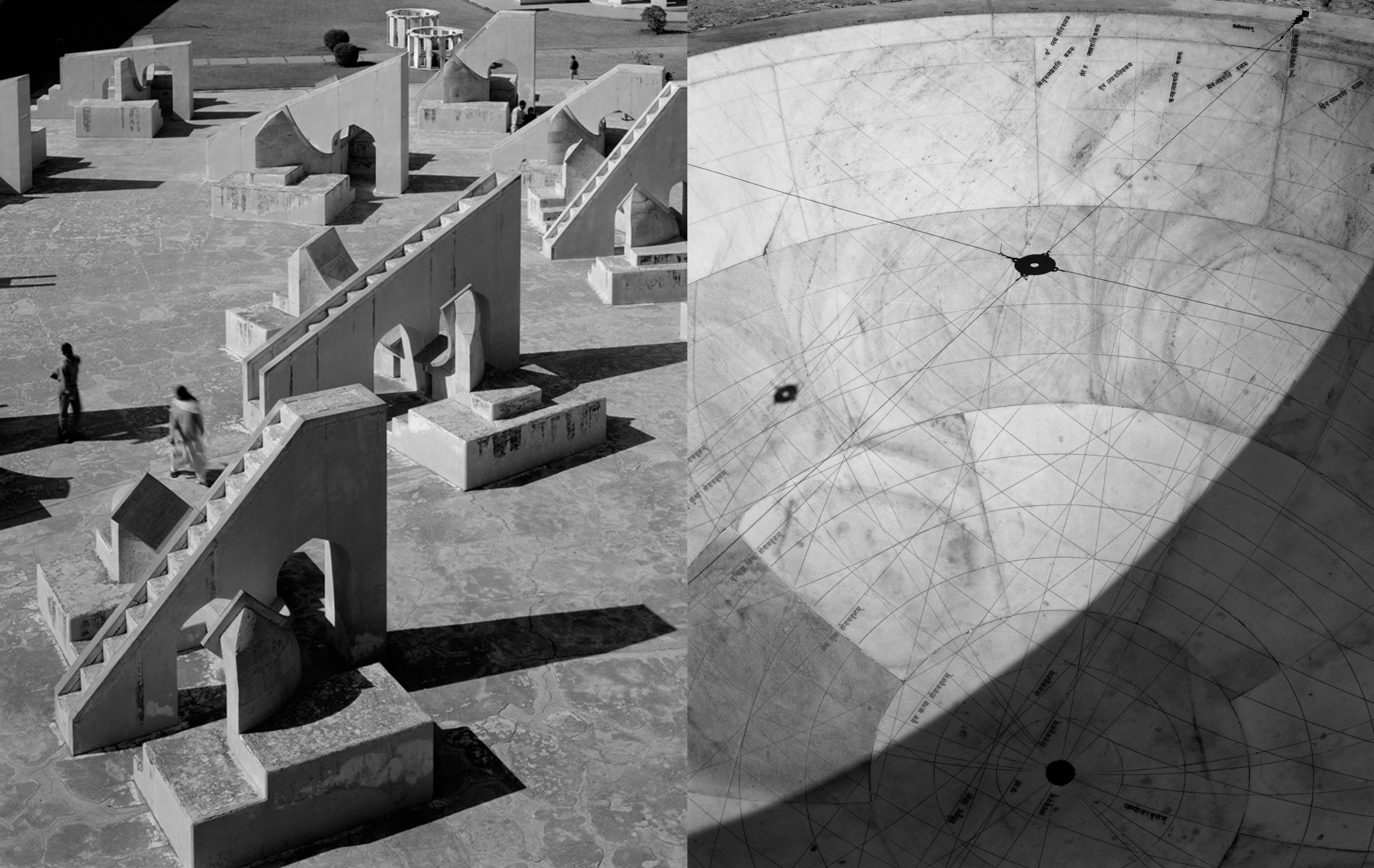

JANTAR MANTAR OBSERVATORY IN INDIA (BOTH 2002). A JANTAR MANTAR IS AN ASSEMBLY OF STONE-BUILT ASTRONOMICAL INSTRUMENTS DESIGNED TO BE USED WITH THE NAKED EYE, AND BUILT DURING THE 18TH CENTURY UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE RAJAH JAI SINGH II.

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

AC /That’s beautiful. As previously mentioned, you've had the opportunity to meet and collaborate with some of the world’s most revered architects. How do you see your role in your relationships with the architects with whom you work?

HB /Every architect is quite different of course, as is their work, and their needs, so the role of the image each time is completely different. I do my own work, but I always respect and feed off the work of the architect. It’s almost like a [musical] score, in a way; you have to understand the material that you’re viewing; you’ve got to respect the period, the concept, but then you sing it with your own voice. And that combination is always different, and quite interesting. So it’s been an incredible 30 years of enriching myself through learning more and more about the ways that architects think about space and society.

FROM LEFT: HEYDAR ALIYEV CENTER, BAKU 01 (2013) AND GLASGOW (2010), ARCHITECTURE BY ZAHA HADID

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

AC /I’m curious to hear about your experiences with some of these incredible architects over the years. For example, looking back, what stands out to you about your collaborations with Zaha Hadid, Peter Zumthor, or others?

HB / Zaha was quite witty and funny. She also pushed me a bit, saying, for example, just go lie on the floor or maybe try a wide angle lens, which was really nice. What I learned from her was to always reach farther. When I see Zaha’s buildings, it’s clear to me she was trying to fight gravity. Today we have all these technical and material options, but the first Vitra building she did was driven by the desire to make something fly, before the technology was really there. She always wanted to aim higher. And that was a consistent part of her work—to never be satisfied. To believe that there is always the possibility—with more thinking, with more technology, with new materials, a new way of drawing—to go farther. And that’s something I learned from her. Don’t sit on what you’ve done; you can do more. It was not something we discussed, but it was something that I felt.

VITRA FIRE STATION 02, ARCHITECTURE BY ZAHA HADID (1993)

Photo by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

With Hejduk, we didn't meet a lot, but sometimes we spoke on the phone. And one day he told me, your photographs [of my work] remind me of my first dream of a building, before the building was made. And that was incredible. If I ever have a bad day, I try to remember these words.

AC /Wow.

HB / That was absolutely wonderful. How I reached that point I don’t know; I was so young and inexperienced, and I didn’t know much about architecture then. Still for me, some of the photographs I’ve done for Hejduk are among the most poetic I’ve ever made. It’s a mystery to me how we communicated at that level.

FROM LEFT: FIELD CHAPEL FOR ST. BROTHER KLAUS AND KOLUMBA MUSEUM, ARCHITECTURE BY PETER ZUMTHOR (BOTH 2007)

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

And with Peter Zumthor, it was different again. I barely knew him when I got a phone call from the publisher Lars Müller, asking if I wanted to do a book project. It was a great commission to work with both Zumther and Lars Müller, and the first day I went to Zumthor’s studio to meet him, we were supposed to go to see his building, but he said, please, can we not go to my building today? I’ve seen it. So instead we listened to music—he loved jazz—and we went for a walk in the landscape and for me, it was very special to get to know him in this way. It informed both the book and our collaboration, which was quite magical in the end.

THERME VALS, ARCHITECTURE BY PETER ZUMTHOR (2006)

Photo by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

AC / That sounds wonderful. It also calls to mind your latest publication, which has just come out. First off: Congratulations! Second, what do you most hope people take away from seeing the publication?

HB /Thank you. The book came from the desire of Marco Iuliano—who is an architect, and a professor at the University of Liverpool School of Architecture and very much interested in representations of architecture—to celebrate the work of the photographer. We often see famous images of buildings—say, for example, the Rockefeller building—but we don’t know anything about the photographer behind that image. So Iuliano plans to make a series of books about these photographers. And for this book, he’s collaborated with Martino Stierli, the head of Architecture and Design at the MoMA, who helped to position my work quite nicely—to place images together which help people to better understand how I approach a space. They’ve both written wonderful essays. The idea is to valorize the role of the photographer of architecture.

LEVITATION 03, PONTE SANT’ANGELO, ROME. SCULPTURES BY GIAN LORENZO BERNINI (2020)

Photo by Hélène Binet; Courtesy of ammann gallery

AC / A publication like this is also an interesting opportunity to look back on one’s path. With that in mind, what are some of the biggest lessons you've learned over the years as a photographer?

HB / The lesson for me is that, when you always try to get closer to a point that you can never reach, that desire, or task—especially when it’s something that pushes you all your life—makes what you do meaningful. There is the hope that maybe one day, with one image, you will achieve one line that will be more like calligraphy than a photograph. But it is a lifetime project. It’s like trying to grasp the horizon. That's a little bit what it is like to photograph a space for me; the desire is strong and intoxicating, but the goal is always a little bit at a distance.

Another lesson is that it is important to try to keep your eye, your gaze, fresh. I think perhaps the reason for the magic when I photographed Hejduk’s work years ago was that I was a young photographer with a fresh gaze. This becomes almost impossible if you’re 64, but you can try to do things to refresh your vision of the world.

HUMBLE B AND HUMBLE C, SUZHOU GARDENS (2018)

Photos by Hélène Binet; Courtesy ammann gallery

AC / I have one last question for you. The world can feel quite challenging these days, given the many ongoing and urgent crises. What gives you hope?

HB /My generation grew up with the sense that we were going to add something positive to the world. But these days, sometimes I think hope is difficult; we need to act. Action is more important than hope.

In my private life, that means one thing. In my professional life, the only thing I can do is to be true to my work—to be very honest, to give myself over fully to a form of expression and beauty that can perhaps make people feel human. That can remind them that they exist, that they, we humans, are strong and capable of great things.

I am not a reportage photographer. I do not go through war zones or document the destruction of the forests. But perhaps by allowing people to find themselves for a moment, to remember their humanity, that is my contribution. There is strength in our humanity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and flow.

Hélène Binet is represented by ammann gallery. To learn more about the artist, visit helenebinet.com Binet's new book is available now via Lund Humphries.